Last month, Bankrate reviewed the history and persistent legacy of “redlining,” a longstanding discriminatory practice where financial services, such as mortgages and insurance, are systematically denied to residents of communities with large populations of certain ethnic and racial groups, traditionally through the exclusion of majority-minority neighborhoods from marketing and outreach. In this post we cover the highlights of that history, explore the recent evolution of redlining claims, and share some tips on how lenders can best prevent modern redlining risk.

The History of Redlining

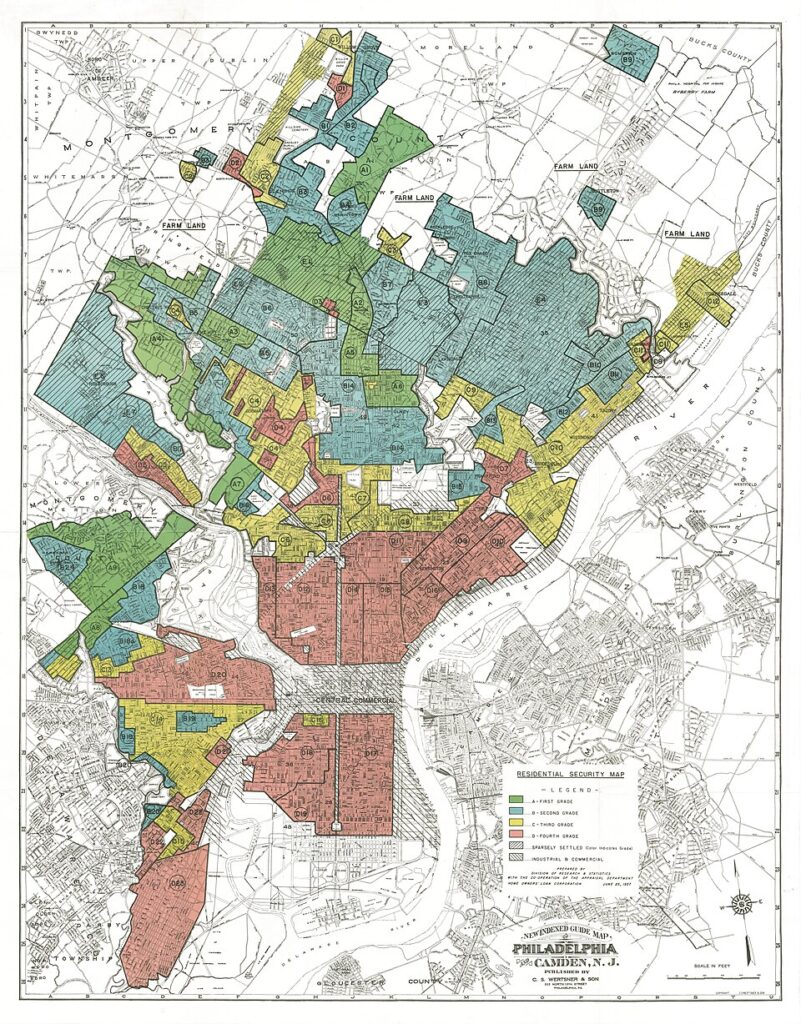

Redlining is a discriminatory practice where financial services, such as mortgages and insurance, are systematically denied to residents of certain neighborhoods based on race or ethnicity. This practice was institutionalized in the 1930s by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a government-sponsored corporation created to prevent mortgage defaults. HOLC created color-coded maps to assess the risk of mortgage foreclosure at the block level in various large cities. Due to the systemic factors driving poverty among minority populations, many of the areas outlined in red in the HOLC maps turned out to be neighborhoods with predominantly Black, Hispanic, Jewish, or immigrant populations. Lenders then began relying on these “redlined” maps to deny access to mortgage credit (including home improvement loans) and other financial services. This practice not only restricted homeownership opportunities for these communities but also led to the deterioration of neighborhoods due to lack of investment and resources.

Although redlining was outlawed by the Fair Housing Act in 1968, its legacy continues to impact communities today. Studies have shown that neighborhoods once marked as “hazardous” by HOLC still experience lower home values, reduced access to quality education, and poorer health outcomes, compared to more affluent areas. Additionally, these communities often face higher rates of poverty and unemployment, perpetuating cycles of economic disadvantage. Efforts to address these disparities include policy reforms like government-backed loans (FHA, VA, RHS) and the Community Reinvestment Act, which encourages banks to lend to underserved low and moderate income areas, and initiatives aimed at revitalizing historically marginalized neighborhoods through investment in infrastructure, education, and healthcare. However, the enduring effects of redlining highlight the need for continued and comprehensive strategies to promote racial and economic equity.

Current Trends: Deliberate Indifference

The ongoing efforts to address redlining have included subtle shifts in the types of evidence used to support redlining allegations. Many “traditional” redlining cases, including some brought as recently as last year by federal regulators, have focused heavily on statistics indicating that a lender’s policies disproportionately affected communities of color. For example, in 2024, the Department of Justice and the Attorney General for North Carolina settled an action against First National Bank of Pennsylvania (FNB) for redlining. The government’s announcement focused on factors like branch location and the perceived impact on generated applications. The settlement announcement described the evidence as follows:

[O]ther lenders generated applications in predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods at two-and-a-half times the rate of FNB in Charlotte and four times the rate of FNB in Winston-Salem. FNB’s branches in both cities were also overwhelmingly located in predominantly white neighborhoods, with the bank closing its sole branch in a predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhood in Winston-Salem in 2021.

The settlement required FNB to make affirmative investments in “advertising, outreach, consumer financial education and credit counseling focused on predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods in those service areas.”

While this approach is outlined as a disparate treatment claim under the framework outlined in Hazelwood School District v. United States, critics of traditional redlining cases like this one have long argued that the approach is a disparate impact claim in disguise that creates an affirmative duty to attract diverse customers. This critique may gain force as federal regulators shift their approach to enforcing civil rights laws.

In some recent rulings on redlining-style cases, courts seem to be focusing not just on statistics, but also on the defendants’ knowledge of those statistical disparities and failure to address them. For example, last March, a U.S. District Court in Illinois denied a motion for summary judgment allowing the National Fair Housing Alliance and other nonprofits to proceed with certain claims against Deutsche Bank National Trust and its service providers, Ocwen Loan Servicing and Altisource Solutions, alleging that the defendants engaged in discriminatory practices by failing to uphold their duty to maintain and market foreclosed properties in Black and Latino neighborhoods to the same standards as those in predominantly white areas, in violation of the federal Fair Housing Act (FHA).

In denying the defendants’ motion to dismiss, the court relied in part on statistical evidence of racial disparity in property maintenance and marketing that – according to the court – a jury could find were not accounted for by race-neutral factors. Notably, the court also noted evidence of the defendants’ knowledge of the problem, citing “Altisource’s directive to remove inappropriate comments from vendor systems, including comments about race” as plausible probative evidence for a jury to find “the servicer defendants’ awareness of the potential for race-based discrimination.” The ruling suggests that courts may rely on similar evidence of deliberate indifference to support disparate treatment claims.

Current Trends: Digital Redlining

While traditional redlining cases have relied heavily on evidence related to a lender’s physical footprint, such as the location of branches and loan officers, in the last few years plaintiffs have increasingly turned to allegations of “digital redlining,” namely the use of digital technologies in ways that perpetuate inequities among marginalized groups, even against financial institutions that lack any formal physical presence.

For example, in a recent class action lawsuit alleging mortgage discrimination by Wells Fargo, the plaintiffs argue that the bank’s use of automated underwriting technology disproportionately sent Black and Latino applicants to higher-risk classes, subjecting them to more underwriting scrutiny than other applicants and resulting in higher denial rates. In court documents, plaintiffs alleged that the underwriting system relied on discriminatory factors, stating:

the coding and machine learning endemic to the [] algorithmic underwriting platform were—byte by byte— stuffed chock-full of Wells Fargo-generated geographic, demographic, racestratified liquidity, appraisal, and other “overlays” that Wells Fargo knew served no legitimate underwriting basis …

In response, Wells Fargo called the conflation of the firm’s front-end loan platform, internal and external underwriting systems, and thousands of additional rules and policies “counterfactual and logically incoherent.” The bank alleges, instead, that the scoring model tool challenged in the lawsuit is not a decision engine but rather a workflow tool that merely sorts applicants by the strength of their credit profile and then assigns higher-risk applicants to “more skilled” underwriters. The case is currently pending before the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California.

Notably, even Wells Fargo’s allegation that the only potential harm is to be assigned to “more skilled” underwriters may itself invite discrimination claims, as recent cases have relied on increased scrutiny as a harm in its own accord. For example, in Huskey v. State Farm Fire & Casualty Company plaintiffs allege that State Farm’s automated fraud detection systems subjected Black applicants to a higher level of scrutiny than their White counterparts (based, allegedly, on disparities related to issues like less accurate voice recognition and uncommon names), resulting in extended claims processing and corresponding delays. The case also argued that subjecting Black claimants to greater rigor creates vicious cycle of disparity:

Biased antifraud algorithms become self-[fulfilling]—if there is racial bias in the claims you identify as potential[ly] fraudulent and investigate, there will be racial bias in the claims identified as fraudulent. You can’t find fraud in a claim you don’t investigate. … Thus, where biased claims processing algorithms subject Black claimants to greater scrutiny, more fraud will be found among Black claimants, resulting in continuing and increasing scrutiny of Black claimants.

A similar argument could apply to workflow cases like the one against Wells Fargo, where plaintiffs may argue that a system that results in routing minority applicants to a more rigorous process (e.g. “more experienced” staff) may actually result in inflated risk findings for that applicant group which may, in turn, be used to justify further security and delays. What’s more, increased scrutiny and delays in processing may lead to higher rates of applicant churn, which could then invite claims of discouragement.

Preventing Modern Redlining Risk

So, what do these trends teach us about preventing redlining risk in the modern environment? Below we highlight three key strategies to detect and address these risks for lenders:

- Review the entire lending lifecycle

One clear lesson that has emerged from recent discrimination cases is that redlining-style risk is no longer limited to lending outcomes, advertising, or office and staff locations. Increasingly, plaintiffs are scrutinizing practices at many stages in the application process, including fraud tools and workflow aids. As in the Wells Fargo and Huskey cases above, processing tools that may inadvertently subject protected classes to more arduous reviews or additional steps may invite legal scrutiny, even if they are not directly related to the decisioning process. These cases highlight the importance of proactive disparity monitoring to ensure that there is nothing in the lifecycle of the lending process that may be causing undetected disparities.

- Show protective action on potential sources of disparity

Once proactive monitoring is in place to detect disparity-driving tools or factors, it is then extremely important that lenders be prepared to swiftly and effectively address any drivers of disparity. As some of the above-discussed cases have shown, being aware of a potential source of disparity and doing nothing to address it can lead to allegations of deliberate indifference to a known discrimination risk. For that reason, tracking, measuring, and carefully documenting any efforts to address detected hot spots is a key step in preventing potential legal risk.

- Understand and scrutinize vendors and vendor tools

Similarly, several of the cases discussed above show the importance of scrutinizing any vendor tools implemented at any step of the lending lifecycle. Fraud-prevention or workflow optimization tools that were once seen as outside the scope of fair lending reviews are now potential drivers of disparity that could result in redlining or similar claims. Even if the tools are built and provided by a vendor, under both third-party risk management and model risk management regulatory guidance, the lender is still directly responsible for overseeing both the tool and the vendor to prevent, detect, and remediate any potential fair lending concerns. For that reason, it is pivotal that lenders take the time to understand and document the nature of these models and tools, including the specific safeguards that the vendor has implemented to address fair lending risk. In addition, through the vendor oversight process, lenders should also ensure that their vendor contracts require vendors to flag any identified fair lending risk issues, as well as the steps the vendor is taking to address them.

Each of these steps will enable lenders to not only address fair lending risk but also ensure that their policies and vendor partnerships are optimizing their lending lifecycle to accurately assess and serve as many qualified applicants as possible.